Plato was an aristocrat by both birth and temperament, and was born in democratic Athens. Plato became a disciple of Socrates, accepting his basic philosophy and dialectical style of debate.

After Socrates’ execution in 399 BC, Plato, fearing for his own safety, and in all disillusionment, set himself for long travels temporarily abroad to Italy, Sicily and Egypt. In 388 BC, Plato, after his return to Athens, founded The Academy, the institution often described as the first European University. Plato died at about the age of 80 in Athens in 348 or 347 BC.

- Events that influenced Plato’s thoughts

- Important books by Plato

- Theory of Forms/Ideas

- Allegory of the cave

Events that influenced Plato’s thoughts:

- Decline of Athens and its defeat in the hands of Sparta

- Corruption and nepotism among the ruling class

- The emergence of democracy

- Death of Socrates in the hands of the state.

Important books by Plato

- The Republic: Plato’s most famous work outlining his theory of justice, the ideal state, and the philosopher-king concept.

- The Laws: His last and longest dialogue, offering a practical blueprint for governance under the rule of law, emphasizing moderation over idealism.

- The Statesman: Discusses the art of statesmanship and differentiates the true ruler from mere politicians and tyrants.

- The Apology: A dramatic account of Socrates’ defence speech during his trial, illustrating the philosophic quest for truth and moral courage.

- The Phaedo: Depicts Socrates’ final moments, discussing the immortality of the soul and the philosopher’s attitude toward death.

- The Crito: A dialogue on obedience to law and civic duty, where Socrates refuses to escape from prison on moral grounds.

- The Protagoras: A debate between Socrates and the sophist Protagoras on virtue and relativism.

Theory of Forms/Ideas

Theory of Forms or ideas is at the centre of Plato’s philosophy. All his other views on knowledge, psychology, ethics, and state can be understood in terms of this theory.

Plato distinguished between two levels of reality:

- The World of Appearances (Sensible World): The material world we perceive through our senses — changeable, imperfect, and transient. Objects here are mere shadows or copies of higher realities.

- The World of Forms (Intelligible World): A higher, eternal, and unchanging realm containing perfect “Forms” or “Ideas” (e.g., Beauty, Justice, Equality). These Forms are the true reality; the physical world merely participates in or imitates them.

Thus, while individual beautiful things come and go, the Form of Beauty itself is eternal and perfect.

Following Socrates’ theory of knowledge, Plato argued that real knowledge is fixed, permanent, and unchanging. It belonged to the realm of ‘ideal’ as opposed to the physical world which is seen as it appears. ‘Form’, ‘Idea’. ‘Knowledge’-all constitute what is ideal, and what appears to the eye as actual, is just a reflection of the ideal.

True knowledge is the ideal since it is permanent and fixed. The material world or the sensory world, which appears before our eyes, is merely a reflection, and is temporary and transient.

Plato explains this distinction through Allegory of the cave, where he differentiated between awareness and knowledge.

Plato: Reality is a shadow of ideas.

Plato’s theory of Form is closely related to his belief that virtue is knowledge. The ultimate object of virtue is to attain knowledge; the knowledge of virtue is the highest level of knowledge. Knowledge is attainable. So, the virtue is attainable.

Plato has extended his theory of Form to his political theory. The types of rulers Plato sought to have should be those who have the knowledge of ruling people. Until power is in the hands of those who have knowledge (i.e., the philosophers), states would have peace. Only the philosopher, who has the true knowledge, can truly govern, since he knows what justice and virtue really are. Hence, Plato’s philosopher-king is a ruler whose political authority is grounded in knowledge of the Forms.

Allegory of the cave

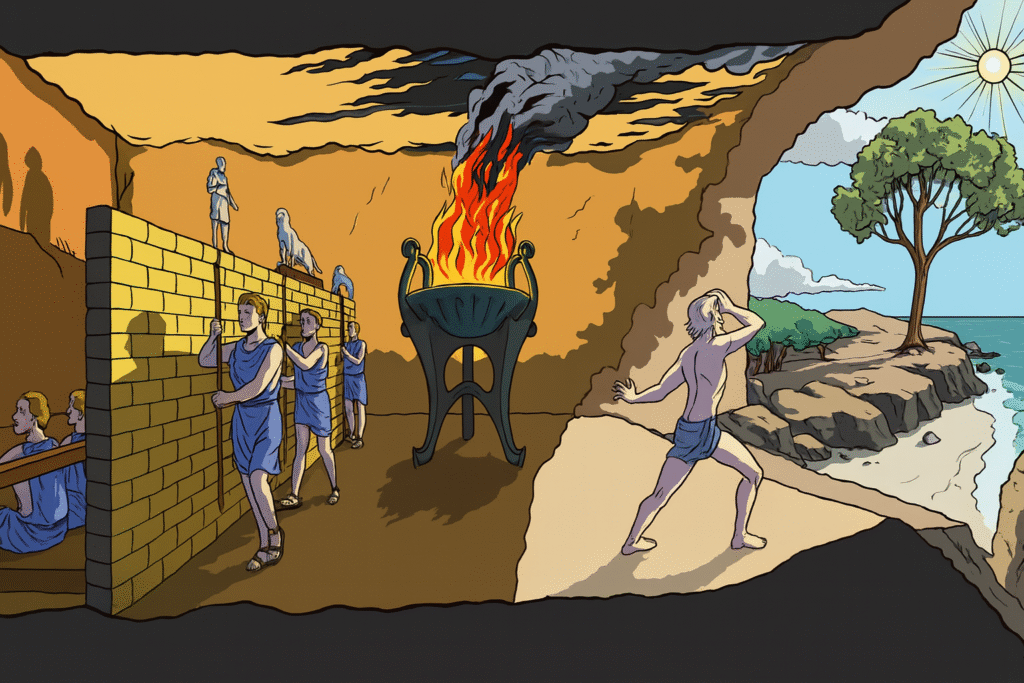

Plato asks Glaucon to imagine a cave inhabited by prisoners who have been chained and held immobile since childhood and are compelled to gaze at a wall in front of them. Behind the prisoners is a fire, and between the fire and the prisoners is a raised walkway, along which puppets of various animals, plants and other things are moved. The prisoners see the shadow cast by puppets on the wall and hear noises made from the walkway. It is obvious that the prisoners would consider those shadows and noises to be the reality.

When the prisoners are freed, initially they would not believe the objects casting the shadow, but would continue to believe the shadow to be the reality. If the men were compelled to look at the fire, they would be struck blind and try to turn his gaze back toward the shadows, as toward what he can see clearly and hold to be real.

Suppose someone forcibly dragged them out into the sunlight, they would be distressed and unable to see anything at all. After some time, when the free prisoners are acclimatized, they will know the real world and realise their previous belief to be mere illusion.

Explanation:

The allegory of the cave symbolises four grades of knowledge through which the mind can ascend to the Ideas, each level being represented by the particular state of men inside and outside the cave.

Men in chains: (Conjecture) This is the first level of knowledge. The shadows and echoes are only reflections of other things. People in this situation are subjected to prejudices, passions, and sophistry, grasping even the fleeting shadows in an inadequate manner. Chained and without desire to escape they cling on to their distorted visions.

The men unbound in the cave: (Belief) The men unbound but remaining in the cave symbolise the second stage of knowledge – belief. When the prisoners turn toward the fire, a visible figure of the sun, and see physical bodies along the way, they recognise that the shadows are merely for dreamers.

Men out of cave: (Reasoning) When one leaves the realm of cave he finds the third degree of knowledge – reasoning. The objects of reasoning, symbolised in the reflections on water of the stars and sun are primarily geometric and arithmetic entities.

Men fully liberated: (Understanding) Men who fully free their minds from the bonds of changing sensibilities and of particular intelligible ascend to the highest grade of knowledge i.e. understanding.

Thus, Plato has explained that real knowledge is attainable and it belongs to the world of ideas. For example, there is a difference between things which are beautiful and what beauty is: What is beautiful, can differ from person to person, since it lies in the realm of opinion while beauty is eternal and lies in the realm of knowledge. Beauty is the reality and not what is beautiful.

Plato’s theory of Form is closely related to his belief that virtue is knowledge. The ultimate object of virtue is to attain knowledge; the knowledge of virtue is the highest level of knowledge.

Plato has extended his theory of Form to his political theory. The types of rulers Plato sought to have should be those who have the knowledge of ruling people. Until power is in the hands of those who have knowledge (i.e., the philosophers), states would have peace.